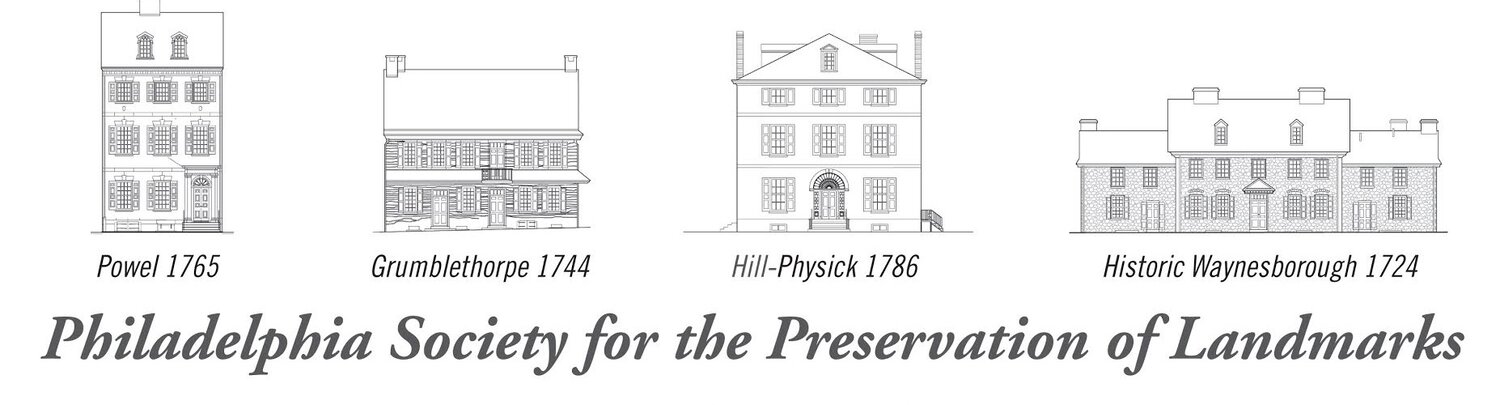

GRUMBLETHORPE

Grumblethorpe

Germantown 1744

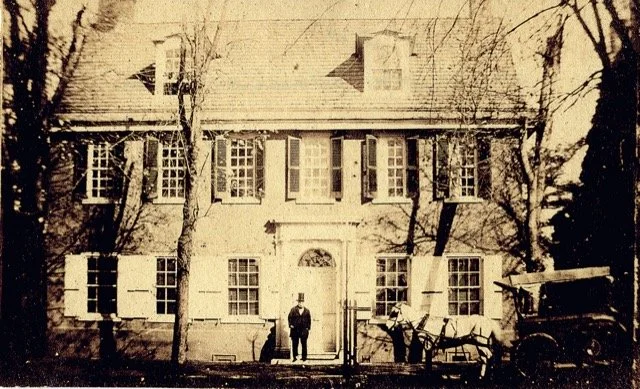

German immigrant John Wister (Johannes Wüster, 1705-1789) built this house in 1744 as a family country home outside of Philadelphia. Constructed of local Wissahickon schist and oak timbers hewn from Wister’s woods, the house is a prime example of Germantown architecture of the period.

Notable features include the stone coursing of the facade, front and rear balconies and the double front entrances. Set on 7.5-acres, the property included a farm, gardens, and orchards with fruit trees to supplement John’s wine importing business.

Known through-out the 18th century as John Wister’s Big House, Grumblethorpe was just one of John’s many properties in Philadelphia and Lancaster. Intended as a summer retreat, the house provided a refuge for the family from the humid Philadelphia summers, and in 1793, the family stayed in Germantown to avoid the yellow fever epidemic.

This house was also taken over by the British and used as one of its headquarters during the Battle of Germantown in October 1777, as John Wister was staying in his Market Street home in Philadelphia and John’s son Daniel and his family had fled to a relative’s house in what is now Lower Gwynedd.

In the early 19th century, Charles Jones Wister Sr., John’s grandson, an astronomer, horticulturalist and inventor, made this Germantown house the permanent family home. He modified the front and back facades to Federal era architectural trends, created additions, and even had an observatory built. It was Charles Sr. who gave the house its new name: Grumblethorpe.

Since acquiring the building in 1941, PhilaLandmarks has restored and furnished the house and cultivated the gardens to reflect the interests and tastes of various generations of Wisters. Coming up in the later half of 2023 and 2024, we will be embarking on further restoration projects at this unique historic property

Grumblethorpe Interior Rooms

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Grumblethorpe Farm and Gardens

Six Generations of Wisters at Grumblethorpe

-

For almost 200 years, Grumblethorpe was the home of the Wister family. Growing up, PhilaLandmarks founder Frances Anne Wister made many visits to Grumblethorpe and to other Wister family homes including Belfield, the home of her paternal grandparents, Wakefield, Stenton, and Vernon.

At age 19, John Wister (1708 - 1789) emigrated from the village of Hilsbach outside of Heidelberg, Germany to Philadelphia in 1727. His brother, Casper Wistar had come to Philadelphia in 1717. Casper quickly became established as a glass manufacturer and accumulated land in the colonial city. We now distinguish between John Wister and Casper Wistar, but the eventual Anglicizing of their names were interchangeable by the brothers and their families.

John Wister owned multiple properties in and around Philadelphia. He and his family spent most of the year in their house on Market Street in Philadelphia, and then spent their summers in Germantown. John owned farmland in both Germantown and in Lancaster.

After his first wife died, John married Anna Catherina Rubincam and built this house in Germantown in 1744 as a family country home. In part to protect his family and remove them “from the plaguing diseases and germs that were prevalent in the central parts of Philadelphia city…" the port neighborhoods in particular.

Constructed of local Wissahickon schist and oak timbers hewn from Wister’s woods, the house was known through-out the 18th century as ‘John Wister’s Big House.’

John Wister’s Public Service and Generosity.* John and his brother Caspar were among the 33 founders of the Fellowship Fire Company, the second oldest fire company in Philadelphia (1738). John and his brother were also among the original contributors to the Pennsylvania Hospital.

John Wister was also a great benefactor to all sorts of local Germantown characters. He was especially friendly with the hermits of the Wissahickon, and gave his financial support to several.

In addition, John regularly sent money to relatives in Germany and he ordered bread to be baked every Saturday which he then passed out personally to the poor people who came to his door.

*The article ”The Wistar-Wister Family: A PA Family’s Contributions Towards American Cultural Development” by Milton Rubincam was the source for the facts in these paragraphs.

-

When John died, the house passed on to oldest son Daniel Wister (1738-1805) who had worked alongside his father in business.

Daniel married Lowry Jones in a Quaker Ceremony. Lowry came from a notable family of Welsh and English descent. The couple had seven children who reached adulthood: Sarah, Elizabeth, Hannah, Susannah, John (who later acquired Vernon House), Charles Jones Wister and William Wynne Wister.

Daniel’s daughter Sally Wister, who lived in the house during the Revolution, kept a diary of her experience during the occupation of Philadelphia. Sally’s diary is one of the only known written accounts of a teenage girl during the American Revolution and it remains in publication today.

Charles Jones Wister (1782-1865) took over stewardship of his father and Grandfather’s house and grounds after his father Daniel died. It was Charles who named the house Grumblethorpe.

Charles was less interested in business and much more drawn to the natural sciences. Charles’ interests were extensive and included mineralogy, botany, chemistry, astronomy, horticulture, invention, geology, beekeeping, clock making and meteorology.

Membership in the Premiere Science and Culture Institutions. Although he was not a professional scientist, Charles was a serious student of a wide range of scientific disciplines and would become one of the principle founders of the Academy of Natural Sciences.

Reflecting his many intellectual interests, Charles was also a member and/or officer of numerous prestigious organizations including the Philadelphia Library Company, the Library Company of Germantown, the Linnaean Society of Philadelphia (whose purpose was the cultivation of the natural sciences), the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the American Philosophical Society. Founded by Benjamin Franklin, its earliest members included George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Marshall. In the 19th century, John James Audubon, Robert Fulton, Charles Darwin, Thomas Edison, and Louis Pasteur were among those elected, along with Charles Wister

Charles was also a member of the Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture, whose founding members included Samuel Powel, Benjamin Rush, George Washington, George Morgan, George Logan, Nicholas Biddle and James Mease. Henry Hill was also a member. So again, we see how the people of our houses crossed paths.

Additions to Grumblethorpe Included an Observatory. Charles made a number of alterations to Grumblethorpe in the 1820s. Along with adding a workshop for building and improving tools and other inventions and objects, Charles built an observatory on the property to witness planetary movements and weather patterns.

A meticulous gatherer of data, Charles was renowned for his ongoing recording of the weather in one of the first systemic approaches to monitoring and collecting changes in weather in Germantown.

Germantown Academy. Charles J. Wister, Sr., was also a trustee of the Germantown Academy and very much involved with the institution. He donated chemicals, various apparatus and maps of Europe, Asia, Africa, and America, along with his mineralogical collection.

*The article ”The Wistar-Wister Family: A PA Family’s Contributions Towards American Cultural Development” by Milton Rubincam was the source for some of the facts in these paragraphs.

-

Charles Jones Wister Sr. had two sons of note by his second wife Sarah Whitesides. His younger son Dr. Owen Jones Wister (1825-1896) married Sarah Butler in 1859 and settled at nearby Butler Place.

Charles and Sarah’s oldest son Charles Jones Wister Jr. (1822-1910) inherited Grumblethorpe.

A musician, writer and artist with a passion for photography, Charles Jr. became known as the ‘Grand Old Man’ of Germantown.

He was the President of the Board of Germantown Academy, where is father had been a longtime trustee. Hundreds of boys during that era recalled Charles Jr.’s weekly visit to wind the clocks.

Charles Jr. has been described by an alumnus of that venerable institution as, “A picturesque figure, a gentleman of the old school, who usually wore red mittens in winter, which made a sensation among the boys…And he took delight in placing mathematical problems on the blackboard at the school with an invitation to the boys to solve them.”*

Charles Jr. was a lifelong bachelor. He would live and enjoy Grumblethorpe house and its gardens and grounds until his death at age 88 in 1910.

It was his final wish, according to his descendants, that "no one but a Wister should live at Grumblethorpe.”

Having no children of his own, Charles Wister, Jr. left the property in Germantown to his two nephews, Alexander Wister and Owen Wister, the son of his younger brother Dr. Owen Wister.

**The article ”The Wistar-Wister Family: A PA Family’s Contributions Towards American Cultural Development” by Milton Rubincam was the source for some of the facts in these paragraphs.

-

Charles J Wister Jr. died in 1910 with no children of his own, so he bequeathed the Grumblethorpe to two of his nephews: Owen Wister (1860-1938), the son of Sarah and Dr. Owen Wister, and Alexander W. Wister (1865-1931), the son of Charles’ elder half-brother William Wynne Wister II.

Owen “Dan” Wister was the most notable of the two nephews. Owen was an only child. His father Dr. Owen Jones Wister (1825-1906) was a physician and the great grandson of John Wister, the first generation of Wisters in America. After getting his medical degree at the University of Pennsylvania in 1847, Owen Jones Wister served as a surgeon in the Navy and then built a successful medical practice in Germantown. He married Owen’s mother Sarah Butler (1835-1908) on October 1, 1859.

Like her husband’s family, Sarah’s parents were also of notable background. Her father Pierce Mease Butler was the grandson and namesake of Pierce Butler of South Carolina who was a United States senator and delegate to the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Sarah’s mother was the famous Shakespearean stage actress, abolitionist and women’s rights activist Fanny Kemble.

It was Owen Wister’s mother Sarah who had the strongest influence on the course of his early life. Sarah Wister’s interests in the arts, culture and the French language led to Owen’s early talents in music and writing and his lifelong interest in the creative arts. Among Sarah’s many friends and frequent guests were Henry James and William Dean Howells. Sarah had grown up surrounded by her mother Fanny’s artistic friends who included Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, William Makepeace Thackery, transcendentalist William Ellery Channing and the eminent paleontologist and geologist Louis Agassiz who was also a friend of Owen’s grandfather Charles Jones Wister.

A Topnotch Education. Notable Friends at Harvard Included Theodore Roosevelt. Like every generation of Wisters, Owen received an exceptional education. After studying at schools in Switzerland and Britain, he attended the prestigious St. Paul's School in Concord, New Hampshire.

Owen moved on to attend Harvard University, where he became a member of both Hasty Pudding Theatricals and Harvard’s oldest and most exclusive “final” club, Porcellian, and it was here that he met and became lifelong friends with the future 26th President Theodore Roosevelt, future Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, the philosopher and father of American psychology William James (writer Henry’s brother), and future Senator Henry Cabot Lodge.

While at Harvard, Wister wrote for both the Harvard Crimson newspaper and for the Harvard Lampoon, demonstrating a clear talent for writing. His mother too was a talented writer who regularly contributed to the Atlantic Monthly magazine, edited by her friend William Dean Howells.

Wister graduated summa cum laude from Harvard in 1882 with a degree in classical music. Determined to pursue a career as a composer and encouraged by his mother, he spent two years studying at a Paris conservatory. But his father induced him to return home to pursue more traditional fields. So Wister reluctantly returned to the United States, working briefly in a bank in New York (a job he hated), before entering Harvard Law School, from which he graduated in 1888.

Health Issues. A Law Degree. Writing About the American West. Like his friend Teddy Roosevelt, Owen Wister also had health issues during this period, in his case neurasthenia (nervous exhaustion). So like Roosevelt, Owen also traveled to the West to improve his health on the advice of his mother’s friend, the prominent physician and pioneering psychologist Dr. S. Weir Mitchell, notable for directing excessively nervous young men to ‘go West’ to engage in rigorous outdoor activity, while advocating that nervous women take to their beds for the “Rest Cure”.

Wister took Dr. Weir’s advice and spent the summer of 1885 at a friend’s ranch in Wyoming (the first of many visits to the West) and this experience changed his life and led to a lifelong passion for and fascination with the West.

In 1889, Wister was admitted to the Pennsylvania Bar and started a legal practice in Philadelphia. Around the same time, he began writing articles and short stories of his experiences out West. After several stories were published in Harper’s Monthly, Wister gave up his law career and embarked on a full-time career as a writer.

His greatest success came in 1902 with the publication of “The Virginian” which became an immediate sensation. This groundbreaking ‘cowboy’ novel sold more than 200,000 copies in the first year alone. Never out of print since publication, the book helped shape our idea of the West and inspired the national myth of the American cowboy. Moreover, over the years, millions of people would see four movie versions of the novel. Thousands more would also see the theatrical production on Broadway or performances by touring companies.

Over the course of his long career, Wister would regularly return to Wyoming, keeping diaries, fishing and hunting, and continuing to write. Wister wrote political and social-themed works, short stories, humorous pieces, as well as biographies of American presidents. During these trips West, Wister also formed a close friendship with the artist Frederic Remington who wound up serving as the illustrator of many of Wister’s publications.

Along with the artist Frederic Remington, Owen became friends and communicated regularly over the years with numerous fellow writers who included his mother Sarah’s great friend Henry James, along with Ernest Hemingway, William Dean Howells, Sarah One Jewett. Rudyard Kipling and others.

Marriage to His Cousin Mary ("Molly") Channing Wister (1869-1913). In 1898, Owen had married his cousin Molly after a short four-month courtship. Molly was the first child of William Rotch Wister and Mary Eustis Wister. In fact, Molly’s sister was our founder Frances Anne Wister.

Molly's father was one of six sons of William and Sarah Logan Fisher Wister. Molly and her siblings had been raised at the Belfield estate in Germantown, once the residence of American portrait painter Charles Willson Peale. Molly’s mother descended from William Ellery, a signer of the Declaration of Independence from Rhode Island, and William Ellery Channing, the founder of Unitarianism and an ardent abolitionist.

Owen and Molly Wister’s began their life together living in Philadelphia proper. But when Owen’s mother Sarah Butler Wister died in 1908, the family moved to Butler Place which he had inherited.

Once in Germantown, young Owen would visit regularly his grandfather Charles J Wister and his gardens at nearby Grumblethorpe. Owen had many escapades at Grumblethorpe as a child and he later remembered his grandfather as having a “quizzical countenance, and a shrewd twinkle in his eye” and who wore a broad straw hat and white starched summer clothes.

Molly and Owen Wister had six children together. But Molly would tragically die in childbirth in 1913. Owen would live 25 more years.

Death and Legacy. Mount Wister in WY. Owen Wister died in Saunderstown in 1938 of a cerebral hemorrhage at age 78. He is buried in the Wister family compound at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia.

The year after Owen Wister died, the state of Wyoming renamed an 11,490-foot peak in Grand Teton National Park in Owen Wister’s honor. Wister was an early visitor to the area and of course the writer who celebrated and made the state famous, creating the enduring American myth of the cowboy as folk hero.

Mount Wister is located 5 miles west of Taggart Lake and to the south of Avalanche Canyon. Wister is memorialized also on the Welcome Sign on Lincoln Highway upon entering the nearby town of Medicine Bow. The sign includes one of the most famous lines from the “The Virginian”: "When you call me that, smile!"

-

In later years, Grumblethorpe was divided between thirty-six different Wister descendants, including our beloved PhilaLandmarks founder Frances Anne Wister (1874-1956).

Frances Anne made the wise decision to consolidate the property ownership and she led the effort to enable PhilaLandmarks to purchase this seminal historic house from its heirs.

Again Frances Anne used the same successful approach she used to purchase Powel House of rallying the wealthy elite to contribute funds to purchase Grumblethorpe, her family’s seminal 1744 House whose history included a role in the American Revolution.

In 1941, PhilaLandmarks took title of Frances Wister's ancestral family home in Germantown.

Over the years from 1956 to 1967, PhilaLandmarks raised additional funds and executed a major restoration of the property, positioning Grumblethorpe to become a museum focused on 18th-Century Germantown history. The aim was also to ensure that the property was a resource for the community and our youth in particular as a place of history and agriculture and hands-on learning.

In 2023—2024, PhilaLandmarks will be embarking on a new set of renovations and restorations to ensure ‘Old John Wister’s Big House’ and its extensive grounds and gardens remain in top working condition for our many visitors and constituencies.

A Passion for Horticulture, Botany and Science

-

The Historic Ginkgo Tree and the Wisteria Plant. Across every generation, Wisters were passionate about horticulture, botany and farming. The family’s impact can still be found on the Grumblethorpe property today, including its acres of flower and vegetable beds and the massive fruiting Ginkgo tree that towers over the property. Dating to around 1830, we believe this is one of the oldest female Ginkgo trees in America.

In addition, the beautiful Wisteria plant, the climbing vine whose beautiful blue flowers still bloom on the property each spring, is named after the Wister family.

Today, Grumblethorpe continues its legacy as a working urban farm begun by first generation John Wister and now additionally as an important teaching resource the community.

The Grumblethorpe Elementary Education Program (GEEP) works with local schools to provide hands-on supplementary science and history education.

The Grumblethorpe Youth Volunteer (GYV) Program is a service youth group that cares for the gardens and house through farming, fundraising, and community outreach projects. GYV’s additionally operate an award-winning seasonal organic farm stand.

First Person Accounts. Across the generations, a number of Wisters kept detailed accounts of their observations in diaries and journals many of which are in PhilaLandmarks possession and available for visitors to see and for scholars to review.

As one example, fourth generation Charles kept a diary recording the weather every day for decades. Today, these records are still used by forecasters in the Philadelphia region as a benchmark for declaring the hottest or coldest day on record.

-

English botanist Thomas Nuttall named the plant in the early 1800s. Competing theories of the name pit the two branches of the family against each other. In an 1818 publication, Nuttall claimed the name was to honor American physician, anatomist, vaccination champion and Professor of Medicine at University of Pennsylvania, Caspar Wistar (1761-1818). When asked about the spelling, Nuttall claimed it was spelled “wisteria” because it sounded pleasant. The argument for it being named after the Grumblethorpe Wisters is that Nuttall was friends with Charles J. Wister Sr. and often visited him in Germantown. Charles Sr. was influential in the Philadelphia science community as a founding member of the Academy of Natural Science, member of the American Philosophical Society, and had a forge and observatory at Grumblethorpe to conduct his own scientific observations of the natural world. Regardless of the “true” origin, the genus name Wisteria will remain unchanged.

-

Gardening Trends in the Early Colonies. From 1740 through the 1870s, Grumblethorpe was largely a working farm, used for practical purposes: producing crops and raising animals. Closest to the house would have been a kitchen garden. Plants grown here were used for edible and medical purposes. Ornamental gardens were a luxury only the wealthiest could afford. Any practice cultivation, such as John Wister’s fruit orchard would have used the majority of the farm landscape. Wister’s Woods was a tract of uncultivated woodland that was the back half of the property that ended at the Wingohocking Creek. Having access to this kind of renewable resource allowed for continuing access to raw wood and free grazing land for farm lands.

Daniel Wister’s Farm Journal. Daniel was the first to keep a journal of his gardening activity. His journal shows the first use of flowers by any of the Wisters. Daniel worked with the local seed companies to cultivate a colorful bulb and annuals garden. And he recorded listings of flowers, planting designs and some specific locations.

His first journal entry to mention the use of a flower ‘bed’ was in 1773: "The round bed near the poles" was to be filled with fifteen varieties of carnations.

In the same year, Daniel wrote he introduced yellow, scarlet, and white tulips. In 1774, he planted roses and violets in the "SE bed". He also planted blue and white varieties of hyacinths, scarlet and white tulips, narcissus, polyanthus, and jonquil.

In 1775, Daniel continued to grow these flowers. He writes about planting them near the summer house and near the SE fence, along with planting “Ranunculus, rose roots," snow drops, flags, purple hyacinths, and royal-colored tulips.”

Charles Wister Sr. Although Charles did not take up permanent residence at Grumblethorpe until 1811, his active involvement began after 1806, when he inherited the property from his unmarried uncle William.

Like Daniel, Charles Sr. kept an ongoing garden journal, but it was not until 1813 that he made any detailed mention of any gardening activity with flowers.

Routine farming activities still consumed the largest share of Charles’ time, especially during his early years at the house. Tasks included planting corn, peas, potatoes, and other crops to sell at area markets, cutting the meadow for hay, raising pigs, hogs, and hens for the sale of smoked meats and eggs, and quarrying the property’s native stone.

Charles tasks also included cultivating the farm’s fruit trees: magnolia, apricot, and varieties of plum, peach, pear, apple, prune, and cherry trees.

Charles’ many scientific interests and new technological advancements ensured his gardens and fields were filled with an even greater variety of horticultural plants, flowers, and shrubs which were both attractive and provided an opportunity to enhance his knowledge base, and interact with others in these emerging fields.

Over time, Grumblethorpe gained local acclaim for its horticultural beauty and diversity, which it retained well into the 20th century.

*The source of the information from this section is from Jay Davidson Susanin’s “Grumblethorpe: An Historic Landscape Report,” (1990).

-

Cultivation of Experts. Charles Jones Wister Sr. interacted with, consulted and hosted an extensive range of acclaimed intellectuals who shared his interests in botany, horticulture, mineralogy, chemistry, meteorology, medicine and the natural sciences.

Along with Thomas Nuttell (1786-1859) the world’s expert in the study of plants who named the “Wisteria” vine after the Wister family, Charles’ guests included physician, botanist and Congressman Dr. William Darlington (1782-1863).

After graduating from the University of Pennsylvania with a degree in medicine and practicing for a number of years, Dr. Darlington turned his attention to his other passions. He became an expert on local flora and published numerous works on botany and natural history. Dr. Darlington spoke regularly at the Chester County Horticulture Society and several plant specimens over the years were named in his honor. He was also a member of the American Philosophical Society and both Yale and Dickinson College awarded him Doctor of Physical Sciences degrees.

Charles shared Dr. Darlington’s interest in medicine, as both botanists and doctors analyze the structure of living things. Charles even took courses in anatomy taught by his famous cousin Dr. Casper Wistar (1761-1818).

Thomas Say (1787-1834) was another friend and colleague of Charles Wister. Professor of Natural History at the University of Pennsylvania and an internationally renowned naturalist, Thomas Say is also known as the Father of American Entomology. Wister and Say were both members of the Philadelphia Academy of the Natural Sciences (Say was President) and also members of the American Philosophical Society, where Say was chief curator.

Thomas Say also was invited to serve as the zoologist on numerous early research expeditions to the American West. These included several of Major Stephen H. Long’s explorations to the Rocky Mountains and to the headwaters of the Mississippi. More than 1,400 species were first discovered and described by Say during these and other trips.

Swiss born naturalist Louis Agassiz (1807-1873) was another guest of Charles J. Wister.

When Agassiz first came to America to deliver lectures at the Lowell Institute in Boston, he took America by storm. He was soon appointed Harvard Professor of Zoology and Geology.

Agassiz was passionate about the natural world and made nature popular and appealing to the public. Like Charles Wister, he too had a passion for the meticulous recording of data. Agassiz described and analyzed all aspects of marine biology including freshwater living and fossil fishes and he also made significant contributions to the new fields of study of the ice age, glacial geology and climate warming.

Agassiz was also a founding member of the National Academy of Sciences and he and Charles were both members of the American Philosophical Society. The Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard was founded by Agassiz.

But Agassiz also believed God’s hand was visible in all creation and he was a denier of Darwin’s theory of evolution, which complicated his legacy, despite his extraordinary range of accomplishments.

The celebrated mineralogist and Professor at Bowdoin College Parker Cleveland (1780-1858) was another close friend and colleague of Charles’ Wister. Charles attended Professor Cleveland’s lectures in Philadelphia in 1814 and later supplied Cleveland with information for his book on American mineralogy, the first book on the topic.

Charles frequently met with his cousin, friend and neighbor Reuben Haines III (1786-1831) who lived nearby Wyck House. Haines was a founding member of the Academy of Natural Sciences and the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, so he and Charles had much to talk about.

Through Rueben, Charles became friends with the writer, teacher and transcendentalist Bronson Alcott (1799-1888). Haines had invited Alcott to come to Germantown from Boston to teach at a small private school in Germantown. Alcott brought his wife Abigail who helped him at the school. The young couple also started their family here, including daughter Louisa May Alcott, who was born on November 29th, 1832. Louisa of course later became renowned worldwide for writing the beloved book Little Women.

A Passion for Clockmaking and Astronomy. Charles Wister was greatly interested in clocks and the concept of time. He cultivated a close friendship with the famous clockmaker, machinist and inventor Isaiah Lukens (1779-1846) who grew up in Montgomery County and learned how to construct clocks and watches from his father. Lukens designed many notable clocks over his career including for the Pennsylvania Statehouse, Christ Church and the Athenaeum of Philadelphia, among many other buildings.

Both Lukens and Wister were inventors and members of many of the same science organizations In fact, Charles designed and built his own observatory on the grounds of Grumblethorpe in part to monitor the sun crossing the zenith every clear day. He issued bulletins of the time, and every clock in Germantown was set by his standard.

Charles’ new observatory was equipped with a telescope, through which he also watched the skies and weather patterns. He often invited Harvard educated astronomer and Professor Sears Cook Walker (1805-1853), who also worked at the U.S. Naval Observatory, to visit and experience his new observatory.

Charles Wister himself tracked weather daily as an unpaid volunteer and sent his monthly recordings to the Surgeon General’s office of the War Department which then maintained a weather service.

Many of Charles’ first person observations and writings on weather can be found today in the extensive Wister family collection at Grumblethorpe.

*The source of some of this information from this section is from Jay Davidson Susanin’s “Grumblethorpe: An Historic Landscape Report,” (1990).

The more detailed biographical information on all of these experts above is widely available on numerous websites.

-

The contributions of the Wister family to nature, botany and horticulture continued in subsequent generations. Most notably, 5th generation John Casper Wister (1887—1982). The younger brother of our founder Frances Anne Wister, John Wister became one of the country’s most honored horticulturalists. Wister’s long and exceptional career spanned 70 years as a landscape architect in the United States and England and his research in cross-breeding produced hundreds of new, hybrid species of plants and flowers.

From the time he was a young boy, John was passionate about nature, botany and horticulture. After graduating from Harvard University in 1909, John continued his education at Harvard’s School of Landscape Architecture. On July 10, 1917, he enlisted as a private in World War I. Letters John wrote during the war, reveal that even during the war Wister was thinking about and kept in contact with his passion for plants and flowers. What’s more, during his leave time, Wister would visit the famous gardens of Europe.

Director of Swathmore College Horticulture Foundation. Among the many contributions John Wister made to local Philadelphia horticulture were to the campus of Swarthmore College. In 1930, the college named Wister as the first Director of the Arthur Hoyt Scott Horticultural Foundation. Wister served as head of this institution for more than 50 years.

Through-out his years of leadership, John had an enormous impact on the Foundation and horticulture. What’s more, he was a hands-on leader and operated much like his sister (and our founder) Frances Anne Wister. In fact, John C. Wister personally landscaped the entirety of the Horticulture Foundation’s 240 acre public garden, with its 5,000 species of trees and shrubs.

The College's nationally-renowned Arboretum is one of the key reasons Swarthmore College is often referred to as “the most beautiful college campus in America.”

Director of the John J. Tyler Arboretum. In 1946, Wister took on yet another significant responsibility. He was named the first Director of the 600 acre John J. Tyler Arboretum in Lima, Pennsylvania. In addition to planting the collections of magnolias, cherries, crabapples, lilacs, conifers, and rhododendrons that are still on the grounds today, Wister also mapped out the routes of all the hiking trails. Once again, Wister remained in charge for a lengthy period of service — 22 years until 1968.

The Wister Education Center and Greenhouse is named after John C. Wister. As is the Woodland Garden, which he and his wife Gertrude Wister created and which is on the grounds of the couple’s former home. A nationally recognized horticulturist and author herself, Gertrude served on the Board of Trustees for the Tyler Arboretum for more than 25 years, starting in 1960, the year she also married John C. Wister.

Other Significant Leadership Roles. John C. Wister served as Secretary of the American Rose Society, President and Founder of the American Iris Society, and Secretary for 24 years of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society. He was additionally deeply connected with the John Bartram Association in Philadelphia. Moreover, Wister was active in most major scientific and conservation groups, holding memberships in 50 horticultural societies and 30 scientific organizations.

Winner of Every Major Award. During his long career, Wister was the first recipient of the four major horticultural awards: the Liberty Hyde Bailey Medal, presented by the American Horticultural Council; the Scott Garden and Horticultural Award; the A.P. Saunders Memorial Medal of the American Peony Society; and the Honor Award of the International Lilac Society.

In addition, in 1966, the Brooklyn Botanic Garden awarded its prestigious Garden Medal to John C. Wister for his distinguished service to the field.

That same year the Royal Horticultural Society of Great Britain dedicated its Daffodil and Tulip Yearbook to him, the first time an American gardener had received that honor.

The Legacy Continues. Today, Grumblethorpe continues its legacy as a working urban farm and teaching resource. The Grumblethorpe Elementary Education Program (GEEP) works with local schools to provide hands-on supplementary science and history education.

The Grumblethorpe Youth Volunteer (GYV) Program is a youth service group that cares for the Wister family gardens through farming, fundraising, and community outreach projects, including running an award-winning seasonal organic farm stand.

Through these and other public programs PhilaLandmarks honors the Wister legacy in the fields of horticulture, botany, agriculture, history, science, education and teaching across many generations.

Grumblethorpe & the American Revolution

-

It was during Daniel’s stewardship that Grumblethorpe and the Wister family were confronted with the reality of the Revolutionary War. A period of great stress for the family.

While his father Old John Wister remained in his town house in Philadelphia, once word came that the British had entered the city, Daniel, Wister, his wife Lowry Jones Wister (1743-1804), and their five children left Grumblethorpe for North Wales in Gywnedd Township.

They would stay with the Foulke Family, relatives on Daniel’s wife Lowry’s side, to ensure they were far removed from Germantown and out of harm’s way.

Hannah Foulke lived there with her three adult children. Her husband William had died in 1775. Her husband had built their two-story stone farm house in 1718 on the site of his Welsh-born grandfather's original log cabin. The house had four rooms on each floor and the Wister family moved into half of the house.

The Wister house in Germantown, Grumblethorpe, had been left in the care of a German female servant, Justinia. But soon, the British would arrive in Germantown, and begin commandeering many of the area houses, including Grumblethorpe, as they prepared for battle with the Americans.

-

Sally’s First Person Account of Life During the War. Once safely ensconced in the Foulke’s house in the countryside, Daniel Wister’s oldest daughter Sarah “Sally” Wister (1761-1804) started a diary documenting this disruptive period in her family’s lives, written as a series of letters to her childhood friend Deborah Norris (later Deborah Norris Logan).

Sally’s 48-page Diary is notable as one of the few, if any, written accounts of a teenage girl during the American Revolution.

As Quakers, Sally and her family removed themselves as much as possible from the British Occupation of Philadelphia from September 1777-June 1778. Rural farm life was significantly different than living in a metropolis like Philadelphia, which she makes clear in her writings about her daily experience.

The only form of entertainment from the monotony and the looming dread of war was the occasional visit from Continental officers. Though the Wisters remained neutral and pacifist by not actively engaging with the war effort, Sally’s writings make clear she was sympathetic to the American side.

Sally was smart and educated like all Quaker girls and that’s clearly evident in her charming, witty text. During her family’s stay at the Foulke House, American officers were periodically quartered at the house, and Sally’s Diary provides a lively mix of the day-to-day life in the household.

Her diary is full of entertaining observations of a 16-year-old girl, providing readers today with a behind-the-scenes, engaging, accessible perspective of life during the Occupation.

Keeping Her Friend Updated. Once regular mail delivery had ended, which disrupted her regular correspondence with her close friend “Debbie.” Sally wanted to continue to keep her friend abreast of everything that happened. Here’s Sally’s own explanation in her Diary:

"Tho' I have not the least shadow of an opportunity to send a letter, if I do write, I will keep a sort of journal of the time that may expire before I see thee: the perusal of it may some time hence give pleasure in a solitary hour . . ."

The First Public Girls School on the Continent. A descendant of notable colonial ancestry, ‘Debbie’ Norris and Sally had met at the Philadelphia Quaker school run by the eminent French Huguenot teacher, writer and abolitionist, Anthony Benezet.

Established in 1755 and patronized by the most prominent families, the school was the first public girls’ school in the colonies. Benezet later founded the Negro School at Philadelphia for black children.

At school, Sally was taught the basic subjects, but she also received instruction in the higher classic and literary studies, as her Journal indicates she had knowledge of French and Latin. She also quotes poets and references books and popular periodicals.

War Comes Close. It was not for long before the peace and quiet ended at the Foulke household and the sounds of war are heard. Sally writes that the families are startled by "a great noise." Soon a "large number of waggons" appeared, and three hundred of the Philadelphia militia rode up to the door begging for drink.

At first, Sally is "mightily scar'd", but after seeing the officers appeared to be gentlemanly, her "fears were in some measure dispell'd, tho'" her "teeth rattled," and her "hand shook like an aspen leaf."

That evening, still more excitement. The gallant General Smallwood, commander of the Maryland troops and his large guard of soldiers, arrive to take up headquarters on the Foulke property.

Sally writes, “The yard and house were in confusion, and glitter'd with military equipments." And "There was great running up and down stairs…"

Upon this closer-up view, Sally becomes reconciled to the troops. "They eat like other folks, talk like them, and behave themselves with elegance; so I will not be afraid of them, that I won't."

Three future governors are among those mentioned in Sally’s text: Colonel James Wood of VA, Major Aaron Ogden of NJ, along with General Smallwood of MD.

Sally’s most engaging text comes in describing her flirtations with the handsome young officers who appeared periodically at the house. Sally is especially smitten by the charms and “engaging countenance” of Major William Truman Stoddert, nephew of the General and a descendant of one of MD’s best families.

While Major Stoddert later that night "appear'd cross and reserv'd." Sally learns from one of the Captains, that the Major is "very bashful; so much so he can hardly look at the ladies."

Soon the Major makes himself very agreeable. And Sally writes humorously, “No wonder; a stoic cou'd not resist such affable damsels as we are." She finds him "very clever, amiable, and polite. He has the softest voice, never pronounces the R at all."

At the end of a week, Sally informs her friend, "Another very charming conversation with the young Marylander… He has by his exceptionable deportment engag'd my esteem."

The General Receives Orders to March. In early November, Sally writes that she is "very sorry; for when you have been with agreeable people, 'tis impossible not to feel regret when they bid you adieu, perhaps forever."

After the families said their good byes, Sally writes, "Our hearts were full. I thought the Major was affected…I wonder whether we shall ever see him again."

On the 5th of December, she is again alarmed on hearing that the British have left the city to attack Washington and his troops. "What will become of us only six miles distant? We are in hourly expectation of an engagement. I fear we shall be in the midst of it."

The Major Returns, Then Departs. On the evening of the 6th, Sally is much upset to see “Major Stoddert return ill with fever, brought on by exposure to cold and fatiguing camp life. He is no longer "lively, alert and blooming," but "pale, thin, and dejected, too weak to rise."

On December 13th, Sally writes: "Ah, Deborah, the Major [Stoddert] is going to leave us entirely -- just going.”

Then at noon: "He has gone. I saw him pass the bridge. . . We shall not, I fancy, see him again for months, perhaps years, unless he should visit Philad'a."

-

Once Philadelphia had been taken over, British General Howe’s next aim was to locate and destroy the Continental army. He divided his troops and left 3,000 in the city and took 9,000 to Germantown in pursuit of the Continental Army.

General Washington had other ideas. He sought to reclaim Philadelphia and attack the city from the northwest, right through Germantown.

Prior to the beginning of the battle, the British units made their way towards the largely vacated Germantown. Five Germantown properties would wind up playing a role in the upcoming Battle of Germantown, including Grumblethorpe.

Grumblethorpe. With Old John Wister remaining at his Philadelphia townhouse and his son Daniel and his family safely ensconced at Foulke House in North Wales (Gwynedd), having fled Germantown on news of the approaching battle, the family country home — our own Grumblethorpe — was taken over by the British.

British Brigadier-General James Agnew was quartered there. His dramatic story involving a shooting, Grumblethorpe and the house’s lone servant Justina is detailed in the chapter below.

Wyck House is another area house that was influential during the Battle of Germantown. This house wound up serving as a field hospital for the wounded.

Wyck House like Grumblethorpe is also connected to the Wister family. One of the daughters in the third generation of occupants, Catherine, married Old John Wister’s brother Caspar Wistar, who had amassed his wealth as a glass-maker and investor in land.

The Deshler-Morris House was occupied by British General Sir William Howe during and after the Battle. Ironically, this house was later occupied in 1793 by George Washington during his presidency when he and others fled the capital in Philadelphia to escape the yellow fever epidemic.

During this period, Germantown became the temporary seat of the federal government. And this house became known as ‘The Germantown White House.’

Cliveden played the largest role amongst the Germantown houses. In fact, much of the Battle of Germantown took place on its grounds.

In the midst of the battle, it was Cliveden where British troops took refuge. They broke in and barricaded themselves behind the house’s strong stone walls for protection, as American troops fired muskets and cannons from the front lawn of Upsala across the street. Yet another Germantown house that played a role in the Battle.

The Fate of Cliveden’s Owner. Benjamin Chew, a top lawyer and Chief Justice of the Province of Pennsylvania, had been taken away from his house in August of 1777 and was being held in preventive detention in NJ for suspicion of loyalist ties to the British.

Chew’s wife and children returned to their Third Street home, which happened to be next door to the house of Samuel and Elizabeth Powel.

After Chew was released from parole in May 1778, he sold Cliveden and moved with his wife and family to their estate in Delaware.

The Chews’ Predicament Brings the Washington and the Powels Together. During this period, the Chews rented their house next to the Powels on South Third Street to among others the Marquis de Chastellux (principal liaison between the French Commander-in-Chief and General Washington) and then to George and Martha Washington, who lived there from November 1781 to March 1782, during the Second Continental Congress.

This close proximity thanks to the Chews further strengthened the friendship between the Powels and the Washingtons. This is another example of the lives and people of our PhilaLandmarks houses and communities connecting together.

In 1797, Cliveden came full circle. The Chews bought back Cliveden, its cannonballs still embedded in its walls.

Like Grumblethorpe and the Wister family, Cliveden House would also remain in the Chew family for generations.

-

General Washington’s Ambitious Plan. The Germantown Battle plan called for four columns of troops to attack the British from multiple directions. The Americans would advance throughout the night and then launch a coordinated assault at dawn. Washington’s hope was that the British troops would be as surprised as the Hessian troops were at Trenton.

Initially the Americans had the British retreating. Generals Washington, General Sullivan and Brigadier General Wayne marched down the main boulevard of Germantown. General Greene did likewise on the American left.

However, there was a considerable amount of fog that morning which hindered the progress of one of the Continentals four columns of militias.

In the dense fog, other columns failed to coordinate. General Sullivan’s line which had earlier that morning routed the British, started taking heavy fire from the shuttered windows upstairs at Cliveden House where Lt. Colonel Musgrave and his 400 British troops were now barricaded, hoping to regroup and hold the house at all costs.

Continental soldiers advanced behind trees and walls. Soon Cliveden was engulfed in fire and smoke, with cannon balls pounding the house and our troops from both sides.

Continental soldiers bravely rushed the doors several times, only to fall back with heavy casualties. Many getting stabbed with bayonets through the windows.

The British continued to resist and soon they received reinforcements. They then were able to finish off the Americans, whose lines had become disoriented in the increasingly dense fog and smoke from munitions.

Some lines had started firing on other lines, mistaking each other for the enemy. This confusion and the close, direct fire together and the heavy casualties they were taking from the British from inside Cliveden forced the Continentals to retreat.

A ‘Defeat’ that Prompted the French to Come to Our Aide. While the Battle of Germantown was a defeat for the Americans, the Continental Army had finally gone on the offensive and attacked the British, which gave our troops renewed confidence.

What’s more, General Howe had once again enabled Washington to escape with his army intact.

The French court too saw that the Americans might prove to be worthy ally after all. It is said they were as much influenced by the sophistication and ambitiousness of the Germantown battle plan, as they were by the American victory at Saratoga.

Death at Grumblethorpe. The Battle of Germantown wound up being a chaotic and bloody fight. But there had been another incident resulting from the fog and inclement weather that had occurred earlier that morning.

This story features British Brigadier-General James Agnew, who had been quartering with his troops at Grumblethorpe.

While riding to battle earlier that day ahead of his troops, the General was taken off-guard and ran headlong into enemy Continental troops some 100 strong. As he turned his horse to escape, Agnew received a fatal shot in his back.

Agnew’s soldiers could not stop the bleeding. So together with Agnew’s faithful servant Alexander Andrew, they carried him back to Grumblethorpe, where Agnew subsequently bled to death on the front parlor floor.

For those curious, yes that stain can still be seen. The story goes that Justinia, the Wister family servant left in charge of the house scrubbed the floor dry of Agnew’s blood. But there remains a pale patch on the parlor floor that is suspiciously in the shape of a pool of liquid.

-

The British Depart Philadelphia. On the June 19, 1778, the Wisters received the news that the British have withdrawn from the city. Sally expresses her delight by writing "This is charmante! . . .It is true. They have gone . . . May they never, never return…I now think of nothing but returning to Philadelphia."

In July of 1778, the Wisters returned to their Philadelphia home. And Sally writes, “Ardent as my desires were to return to this dear city, I did not leave our good and obliging relations and quiet retreat, without regret. I sigh'd, and the starting tear stood trembling in my eye. A tear was a poor tribute to the many happy scenes I have enjoy'd there; yet they shall ever live in my memory.”

She continues with her last thoughts. "I had the satisfaction of finding my friends in possession of health and tolerable spirits. My heart danc'd and eyes sparkled at the sight of the companions of my girlish days. Add to this the rattling of carriages over the streets -- harsh music, tho' preferable to croaking frogs and screeching owls.”

In 1789, after the death of Old John Wister, Sally’s father Daniel made the Germantown house (later given the name of Grumblethorpe) his permanent residence, and here Sally lived the remainder of her life.

As she grew to womanhood, Sally became more serene, but letters in the form of verse written to her brothers show she still retained much of her former liveliness and good humor.

In her later years, Sally appeared little in society and her focus was on her religion. She never married which was not uncommon for Quakers, but it is a surprise for readers of her Diary which revealed her to be a sociable and charming young girl whose naive confessions suggested she had very much enjoyed the company of young men.

However, a wide social and religious gulf separated Sally and Major Stoddert. He was a member of the Church of England, and a soldier, rich in enslaved servants and plantation lands in MD. Sally was a PA Quaker, a Society that believed war was unchristian, and forbade members to marry out of faith. So the two of them were never destined to marry.

A Focus on her Faith and Caring for her Mother. Sally spent the last half of her life caring for her mother and siblings. She wrote often to family and friends and found a close friend in the celebrated Philadelphia physician Dr. Benjamin Rush.

When Sally died on April 21, 1804, only a couple of months after her mother Lowry’s death, Rush wrote in the Philadelphia Gazette, "Died on Wednesday last, Miss Sarah Wister. The distress occasioned by the death of this highly accomplished and valuable lady is greatly heightened by recently succeeding that of her excellent mother.”

Debbie Norris Finally Reads Sally’s Journal. Sadly, Sally’s Journal did not reach “Debbie” Norris its intended recipient until 1830, years after Sally’s death, when Sally’s brother Charles Wister lent it to Deborah, who was now Mrs. George Logan.

After reading it, Deborah wrote Charles that she was “at a loss for adequate expressions…and that together with her memory of the beloved writer, brought vividly to her mind days long since past…”

Happily for history, Sally’s 48-page Diary was published by the Wister family in 1902 and continues to remain in print.

Visitors to Grumblethorpe can see the worn pages of Sally’s actual Journal in person, as well as see her bedroom where she grew up.