HILL-PHYSICK HOUSE

Hill-Physick House

Philadelphia 1786

Built after the Revolutionary War by the wealthy Madeira wine importer Henry Hill, this stunning four-story square brick house is the only free-standing Federal townhouse remaining in Society Hill. The house was named a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

With its commanding entrance and doorway fan transom, its impressive windows, grand proportions and classical lines, the Hill-Physick House is an exceptional example of the Federal style. It’s stately and spacious interior rooms are decorated with outstanding examples of French-influenced Neoclassic furnishings, popular during the period.

Hill-Physick House was later the home of Dr. Philip Syng Physick. Graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, Dr. Physick became one of the foremost physicians of the time and is known as the father of American surgery.

While Henry Hill built the house with the fortune he made importing Madeira wine, he only lived there briefly, succumbing to yellow fever in 1798. The house was purchased by Abigail Physick who in 1815 deeded it to her famous brother. Dr. Philip Syng Physick lived there until his death in 1837.

Wealthy and connected, Dr. Physick hosted the country’s elite at his grand home. Guests included novelist James Fenimore Cooper and deposed king of Naples and Spain, Joseph Bonaparte, medical colleagues like Dr. Benjamin Rush and Stephan Girard, notable wealthy neighbors and even some of his celebrated patients: Dolly Madison, the daughters of President John Adams and President James Monroe, Chief Justice John Marshall and President Andrew Jackson to name a few.

Hill-Physick Interior Rooms

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Photo by Joe Pulcinella

Hill-Physick Garden

Henry Hill: A Fortune Built on Madeira Wine

-

Henry Hill (1732 —1798) was a merchant, politician and Revolutionary War Colonel who became extraordinarily wealthy outsmarting British tariffs by importing Madeira wine.

Born on his father’s tobacco plantation in Annapolis, MD, Hill’s Point, Henry Hill was the second son of Quakers Deborah Moore Hill and Dr. Richard Hill, a physician.

When Dr. Hill and his wife had to leave the colonies and their plantation due to financial difficulties and the harsh penalties for owing creditors, the family dispersed.

Henry and seven of his siblings moved to Philadelphia to be raised by their older sister Hannah and her husband Dr. Samuel Preston Moore. And his two older sisters, Harriet and Mary, accompanied their parents to Madeira, Portugal.

Henry wrote about this separation in a letter he wrote his parents around Christmas of 1742, “…My brother Moore [Hannah’s husband] tells me I must mind the books that I may be a Dr. and I am very willing and wou’d go to Scotland to school or anywhere else where I may be able to know how to be a Doctor like my papa.”

Henry did travel to Scotland for school and from there he wrote his father again, in the Fall of 1746, “I desire of seeing you more until I have done with the schools here…” and hope that “I might come home well educated…after all the expence and Pains that has taken’d upon me.”

After seven years in Scotland including one year at Edinburgh College, Dr. Hill reached out and asked Henry and another son to join him in his new, thriving Madeira wine business.

Dr. Hill had recovered the fortune he’d lost in Maryland, but he needed help managing his expanding wine export operation and its offices in Madeira and London.

Along with his father, Henry’s mother Deborah welcomed him to the island in 1751. She was overjoyed to see her 19 year-old son after so many years, and Henry remained in Madeira for most of the remaining decade.

But sadly during his years in Madeira, Henry’s mother and his only brother passed away, leaving Henry as his father’s sole surviving son.

-

When his father died in 1762, Henry inherited the largest share of his father’s successful Madeira business to run together with his two London-based brother-in-laws. Hill was tasked by his family with returning to Philadelphia to grow the business in the colonies.

There, Hill smartly cultivated lucrative markets, including developing relationships with thirsty colonial Army regiments.

He also sold Madeira directly to the Philadelphia political and social elite which included, Governor John Penn, future Signers of the Declaration of Independence John Hancock and Charles Carroll, financier Robert Morris and notably George Washington, among others.

Because Madeira wine was imported from the Madeira Islands which was not considered part of Africa, it wasn’t subject to British tax, even though Madeira was owned by Portugal, in the Europe mainland. Consequently Hill and his family made a fortune.

-

As early as 1752, Henry’s father had expressed concern that his son needed to find a wife. After he had died, his sisters took up the cause of finding their brother a suitable partner, preferably Quaker.

But Hill’s business responsibilities took over and it was not until 1772, at the late age of 40, that Hill finally met someone he wanted to marry: Ann Meredith, the daughter of Reese and Martha Carpenter Meredith.

Ann’s father, Reese Meredith, was a rich Quaker merchant, who had made his fortune in real estate and shipping, further enhancing Hill social connections. Meredith had also known Hill’s father and been helpful to him during his financial difficulties in the 1730’s.

Though both Ann and Henry were Quakers, the couple opted to be married at the socially more connected Christ Church. Although Ann wound up inevitably being disowned by her Quaker Meeting group when she married, she had followed the path of both of her siblings who had also left the Society of Friends.

Hill’s marriage connected him with two successful and socially prominent brothers-in-law.

Ann’s sister Elizabeth Meredith was married to George Clymer, a future signer of both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, donor to the war effort, and captain of the Third Battalion of Associators, a volunteer military association comprised of upper-class Philadelphians.

In 1789, Clymer was elected to the first U.S. Congress and later, he served in many public roles until his death in 1813, including as Trustee of the University of Pennsylvania.

Ann’s brother Samuel Meredith who had married Margaret Cadwalader, was a partner in Ann’s father Reese Meredith’s extensive merchant and land speculation business, as was George Clymer.

Samuel also served three terms in the Pennsylvania Assembly, was a delegate to the Continental Congress, and was a Brigadier General of the Third Battalion of Associators, serving in four major battles. After the war, at his friend George Washington’s request, Samuel Meredith also served as first Treasurer of the United States.

-

In 1770, Henry purchased a large country property overlooking the Schuylkill River in Roxborough, about six miles from Philadelphia.

His property provided him both a happy retreat and an opportunity to make additional revenue in transportation, farming and breeding horses. Roxborough, as he called it, even had a racetrack which provided Hill with additional income.

Henry’s significant and growing wealth enabled him to enter politics. In 1771, Hill was elected to the prestigious American Philosophical Society. He became Justice of the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas in 1772 and was elected to the Constitutional Convention in 1776.

It was not until 1786, that Hill began building the exceptional free-standing mansion known today as the Hill-Physick House in the newly prestigious neighborhood of Society Hill.

Hill’s neighbors would include the wealthy elite of Philadelphia, including among others, the Powels, the Shippens, Robert Morris, Thomas Willing and his wealthy son-in-law William Bingham.

-

In 1774, Hill had the distinction together with 27 other men as one of the original members of the Light Horse of the City of Philadelphia — the First City Troop. Today, it is the oldest mounted military unit in continuous service to the Republic, participating in every American war.

Two years later, Hill was named a Colonel in the 4th PA Regiment. Hill likely fought in the Battles of Trenton and Princeton.

In addition, during the Philadelphia Campaign in August of 1777, General Washington opted to encamp his army at Hill’s country estate near Germantown, with Hill’s elegant home serving as the General’s temporary headquarters.

Both Washington and French General Marquis de Lafayette quartered there with Hill for a week.

Hill also donated five thousand pounds to the Pennsylvania Bank to provide supplies for the Continental Army, making him along with Samuel Powel one of the top private donors to the war effort.

-

Henry Hill continued to remain on the political stage and in the limelight. Hill was asked to serve on the Board of Directors of the Bank of North America (1781-1792), to which he had been a founding subscriber and donor.

During this period, Hill also continued to serve as a member of the Pennsylvania Assembly, and the Executive Council (1785-1788).

In 1783, together with Benjamin Rush, William Bingham, and others, Hill became a founding trustee of Dickinson College, the first college chartered after the formation of our new nation.

The college is named after Quaker John Dickinson, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and later governor of Pennsylvania, and his wife Mary Norris Dickinson, whose extensive personal libraries were given to the college.

In 1790, Henry’s close friend Benjamin Franklin died and Hill was named one of four executors of his will. The will provided for some endearing gifts, including one for Henry Hill: a silver cream pot with the motto, “keep bright the chain.”

Tragically, three years earlier, on December 11, 1787, Henry’s wife Ann Hill had died of a “tedious and painful illness”, likely grand mal seizures or epilepsy which her father had also suffered from.

Ann died in the house we know today as Hill-Physick, which she had helped plan, design and pay for with her inheritance from her father’s estate. The house was still only partially finished, so Ann never got to enjoy the house in its final form.

Ten months before she died, Ann wrote a letter to her husband outlining the charities she wanted her estate to donate to: the poor of Philadelphia, the public school in Germantown, and to her sister-in-law Mrs. Patsy Moore for “promoting her plan of Female Education.”

Eleven years later, Henry Hill died in the lesser known Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1798. 1,200 people would die along with Hill, who stayed in his house on Fourth Street even after two of his servants had died. He only called on his friend Dr. Benjamin Rush near the end, but refused treatment, despite a visit by his concerned sister.

Sadly, virtually all of the free-standing houses in Society Hill from the colonial era have been torn down. Happily, the Hill-Physick House still stands, the only free-standing house remaining from in Society Hill from that time period.

Philip Syng Physick and his Family

-

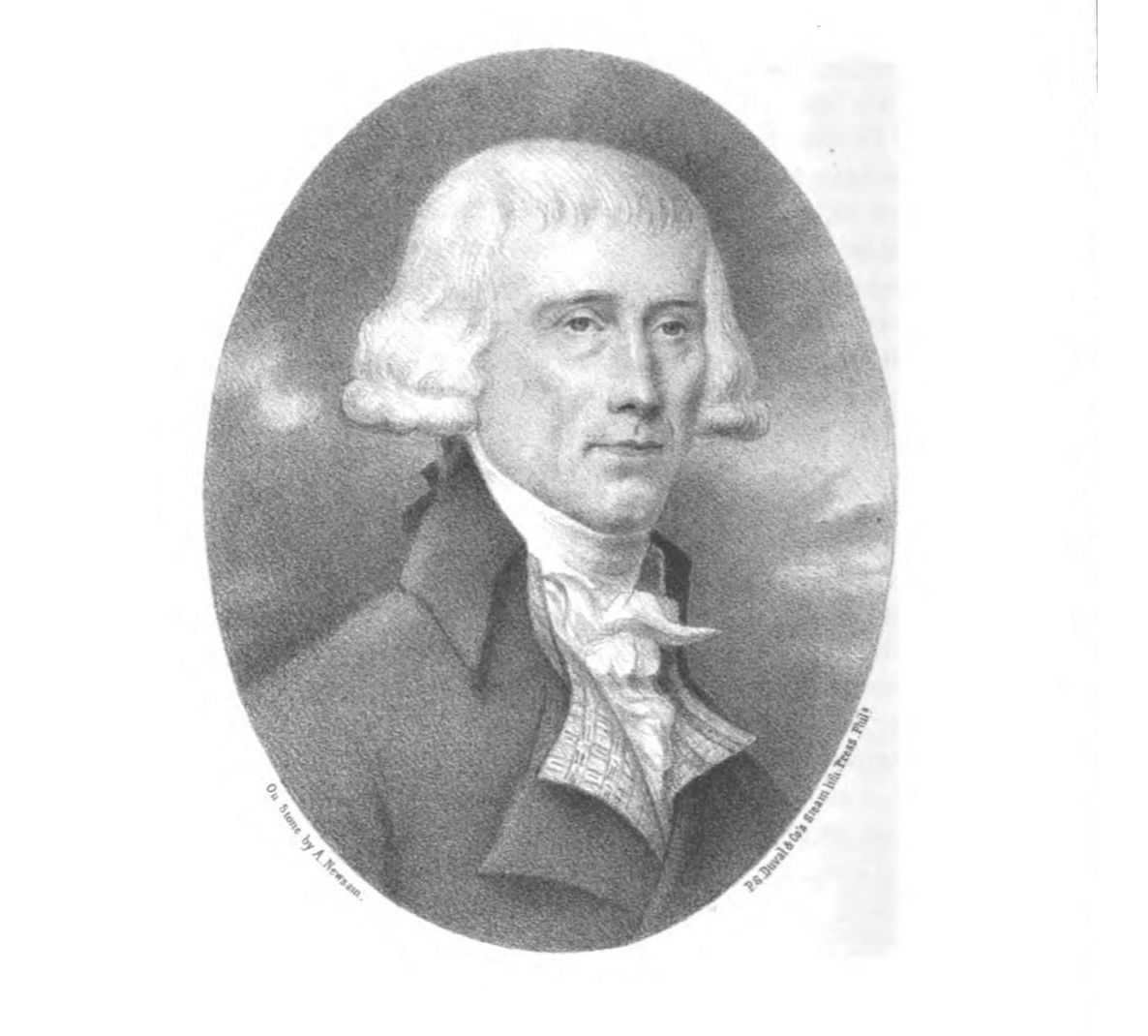

Philip Sing Physick was born in Philadelphia on July 7, 1768, the youngest of four children of Edmund Physick and his wife Abigail Syng. Edmund Physick was a successful businessman, Keeper of the Great Seal for the Penn family and receiver general of Pennsylvania.

In the early 1770’s, the family moved to Governor John Penn’s Lansdowne estate to live in a small house there called ‘The Hut.’ John was the eldest grandson of William Penn. John’s wife Anne, had grown up at nearby Mount Airy.

By moving to the house on the parkland of the Penn’s estate, Edmund could better manage the family’s extensive property and business interests, which he continued to do right through the Revolutionary War.

Young Philip was sent to Philadelphia to be educated at the Friends Academy. There he boarded with Mrs. John Todd and on weekends he walked five miles home to ‘The Hut’, on the west side of the Schuylkill River.

-

Philip’s mother Abigail Syng (1730-1792) was the eldest of an astounding 18 children of Elizabeth Warner and the renowned silversmith Philip Syng, Jr., (1703–1789), whose family had immigrated from Cork, Ireland in 1714.

Syng created the finest sterling silver and gold pieces for Philadelphia’s leading families.

Among his historically most significant silver works was his 1752 inkstand used to sign both the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and the United States Constitution in 1787.

The inkstand is on display in Philadelphia at Independence National Historical Park, along with the Declaration and the Constitution.

-

The renowned silversmith Philip Syng was Ben Franklin’s oldest friend, a relationship that spanned 63 years.

The two were also fellow inventors and members of the prestigious Junto group. Junto members were merchant-class men of different occupations that shared a spirit of inquiry and a desire to improve themselves. They met regularly to discuss and debate the moral, political and scientific topics of the day.

Interested in both science and medicine, Syng was singled out and invited by Franklin to participate in his world famous electrical experiments, earning Franklin’s praise as his “worthy and ingenious friend.”

Like Franklin, Syng was a founding trustee of the University of Pennsylvania (1750), and a founding member of the Library Company, the American Philosophical Society, the Union Fire Company, Pennsylvania Hospital, and in 1752, the Philadelphia Contributionship Insurance Company.

Syng designed the insurance company’s Hand-in-Hand fire mark, which you can see today on the Powel House exterior.

Syng and Franklin were also both Christ Church Vestrymen and in 1747 helped organize the Pennsylvania National Guard, PA’s first state militia.

-

Philip Syng Physick always liked working with his hands and in his younger years expressed a desire to become a silversmith like his revered grandfather Philip Syng. But Philip’s father Edmund was insistent that his son pursue a medical career.

Philip first went to the University of Pennsylvania to study with the notable Dr. Adam Kuhn. Afterwards, he and his father went to London to study with the celebrated surgeon Dr. John Hunter at his school for budding surgeons. In 1790, he became House Surgeon to St. George’s Hospital in London

Philip received his medical degree in 1792 from London’s Royal College of Surgeons and his medical doctorate from University of Edinburgh, then moved back to Philadelphia where his father set him up in an office on 45 Arch Street, likely the same house where he’d been born.

-

In 1800, Dr. Physick married Elizabeth “Betsy” Emlen (1773-1820), daughter of a wealthy Quaker minister. Betsy brought a large dowry to the marriage. She and Philip had four children: Sarah (Sally) (1801-1873), Susan (1803-1856), Philip (1808-1848), and Emlen (1812-1859).

Their eldest Sally married Dr. Jacob Randolph. Susan married Commodore David Conner in 1828. Connor had been twice decorated for his gallant service as a naval officer in the War of 1812. And Philip Jr. became a lawyer and married Caroline Eliza Jackson.

Sadly, Philip and Elizabeth’s marriage proved to be unhappy. After fifteen years, they had grown estranged, which led to their difficult, public separation in 1815.

A Deed of Separation was drafted that included the return of properties from Elizabeth’s original dowry and other assets she’d received from her father’s last will, all of which enabled her to live on independently.

The reason for the separation is unclear. The Deed did not give an explanation, and through Susan’s personal writings, we know that their marriage was acrimonious.

-

Intermarriage was common among the families of the Philadelphia elite. The same names appear in the histories of the four PhilaLandmarks houses. For example, Elizabeth Physick’s family, the Emlen’s, and Samuel Powel’s family were connected by marriage.

Mayor Samuel Powel’s sister Deborah Powel (1706-1730) had married Joshua Emlen. Their son Samuel Powel Emlen and his second wife Sarah Mott were the parents of Elizabeth “Betsy” Emlen, who later became Dr. Philip Syng’s wife.

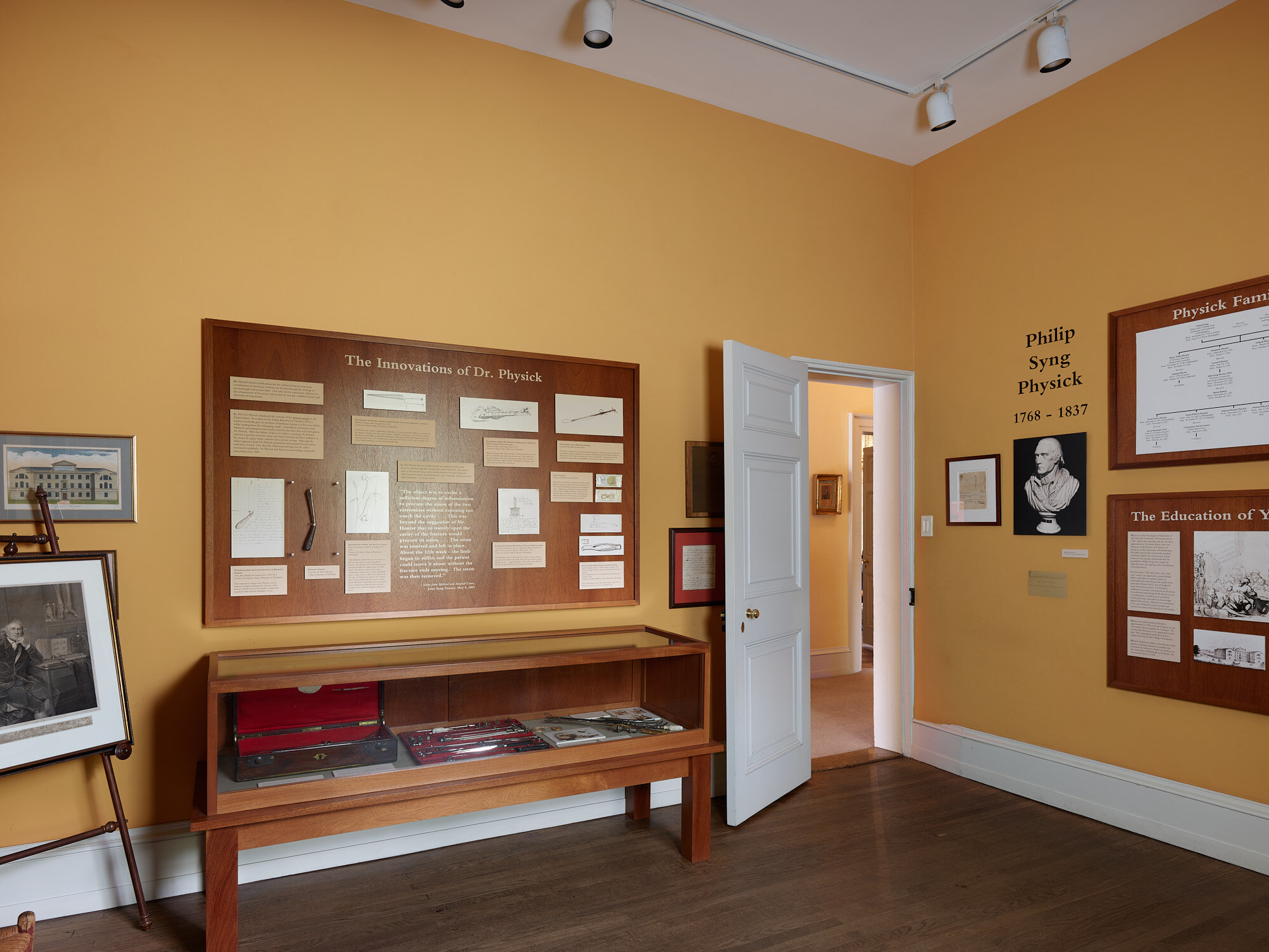

Dr. Philip Syng Physick: A Giant in Medicine

-

Dr. Philip Syng Physick achieved international renown as a surgeon and is considered the father of American surgery.

He was Pennsylvania Hospital’s first Chief of Surgery and also held both the first full Professor of Surgery Chair (1805-1819) and then later took over the Anatomy Chair (1819-1831) at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School, training an entire generation of new surgeons.

Dr. W. E. Horner of Philadelphia described Dr. Physick as, “The universally acknowledged centre and head of surgery of this country. An indescribable interval separated him from everyone else, and yet attracted everyone to him.”

Horner also described his colleague’s skill in the operating room, writing that Dr. Physick had “a hand delicate in its touch and movement and which never trembled or faltered.”

-

Innovative Medical Inventions. Dr. Physick was known both for his skills and decisiveness in the operating room, but also in the mechanics of the art and for the innovative surgical tools he invented. These included the stomach pump, curved needle forceps, absorbent catgut sutures, third molar forceps for tooth extraction, and the guillotine/snare for performing tonsillectomies.

Contributions to Orthopedics and Urology. Dr. Physick also made improvements in the field of orthopedics — splints and traction devices for skeletal dislocations, including for thighs, and for displacement of the foot (‘Pott’s fracture.’) Many of the devices Dr. Physick created and/or enhanced remain in use today.

Moreover, Dr. Physick played a significant role in the developing field of urology. He devised numerous urological procedures and instruments which included clamps and tubes for removing kidney stones. He was unequal in his skill in lithotomy and one of his last operations was the removal of Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall’s kidney stones.

Blood Transfusions. A footnote in the “Philadelphia Journal for the Medical and Physical Sciences” in 1825 credited Dr. Physick as the first person to complete a blood transfusion; though there is not any case history to substantiate this claim. However, this idea may have been introduced to him at the University of Edinburgh, where Dr. James Blundell, the first published account of a successful transfusion, also attended.

Another first. Early in his career, in an attempt to build his practice, Dr. Physick offered the first healthcare insurance package in the country. He advertised that he could take care of an entire family for a year for $20.

Magnanimous Fee Policies. Throughout his career, though he did make a sizable income, Dr. Physick always asked his patients about their financial circumstances, often taking payment in trade or reduced fees if the patient was of limited income. He never accepted payment from clergy or officers in the Army or Navy.

-

Dr. Physick’s inventions did not stop at surgical tools. In 1807, he started reading about the experiments by German scientist Johan Jacob Schweppe to manufacture carbonated water which were based on the discoveries of English chemist Joseph Priestly.

Dr. Physick decided to create his own product for his patients, introducing Dr. Physick Black Cherry Soda. By cleverly adding flavor to artificial carbonated water, Dr. Physick had created America’s first soft drink.

Prescribed for the relief of gastric disorders, Dr. Physick directed his patients to drink his sodas daily at a cost of $1.50/month, creating additional revenue for his practice.

-

Though brilliant as a surgeon, it was Dr. Physick’s exceptional talents and success as a teacher that made him beloved by both his students and colleagues. Part of his appeal was his care and empathy for his suffering patients.

Dr. Physick’s many leadership positions included President of the Philadelphia Medical Society, the first President of the Academy of Medicine (founded in 1797), a member of the American Philosophical Society, an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Medical Society of London (1836), a member of the Royal Academy of Medicine of France (1825) and a member of several other prominent European medical academies.

-

A Maryland Summer Residence. In 1833, Dr. Physick acquired a summer house called Octorara Farm in Cecil County, Maryland to escape the hot Philadelphia summers.

Situated on a hill with commanding views of the Susquehanna River, the property included 201 acres and a Greek Revival house built in 1775 which included numerous outbuildings. Dr. Physick added significantly to the size of the house, as he loved spending time there with his two daughters and their families.

Death. Sadly, after just four summers of enjoyment at his new property, Dr. Physick died on December 13, 1837. The cause was described as ‘hydrothorax’, possibly emphysema.

His funeral was held in his Philadelphia house, as was the custom then. After a reception, the coffin was carried up 4th street to Church Christ burial ground. There were hundreds of mourners following behind: faculty members and trustees, his past students, fellow members of all his various societies and organizations and many friends and patients.

His Will Provided for his Children. Dr. Physick’s will divided his estate into equal shares for his son and two daughters. He bequeathed Octorara Farm to his daughter Susan Physick Conner, the wife of Commodore David Conner, US Navy.

To his daughter Sally Physick Randolph, who had married Dr. Jacob Randolph, he gave the house on 321 South Fourth, now called the Hill-Physick House.

Dr. Physick’s son Philip Syng Physick Jr. took his share of the inheritance in significant monies, stock and other valuables and built a house at 1901 Walnut Street, a large marble and stucco mansion which became known as ‘Physick’s Folly’.

He Also Provided for his Staff. Dr. Physick provided generously for two servants, his housekeeper Anna Marie Shields and another servant Rhoda Poynter. These women played a significant part of his daily life, as he described them in his will as having “so long lived in the utmost kindness and harmony.”

In his will, Dr. Physick directed his son to provide $2,500 to buy them a suitable house to share, in Anna’s name. He also provided furnishings and trust funds for ongoing income.

Of the two women, Anna Marie Shields was given the larger of the trusts and it was said that she had been a sort of companion to Dr. Physick.