A Whirlwind Grand Tour

A Reflection on the Attingham Trust Summer School Course

As I reflect on my experience of the 70th Attingham Trust Summer School course and look back through my scribbled notes lined in nearly three full notebooks, I find it challenging to concisely sift through the sheer breadth of material and information I absorbed throughout those sixteen days in the country-sides of Sussex, Derbyshire, and Norfolk. Many have likened this program to a crash master’s course in the study of Historic Houses, to which I can attest is an accurate description.

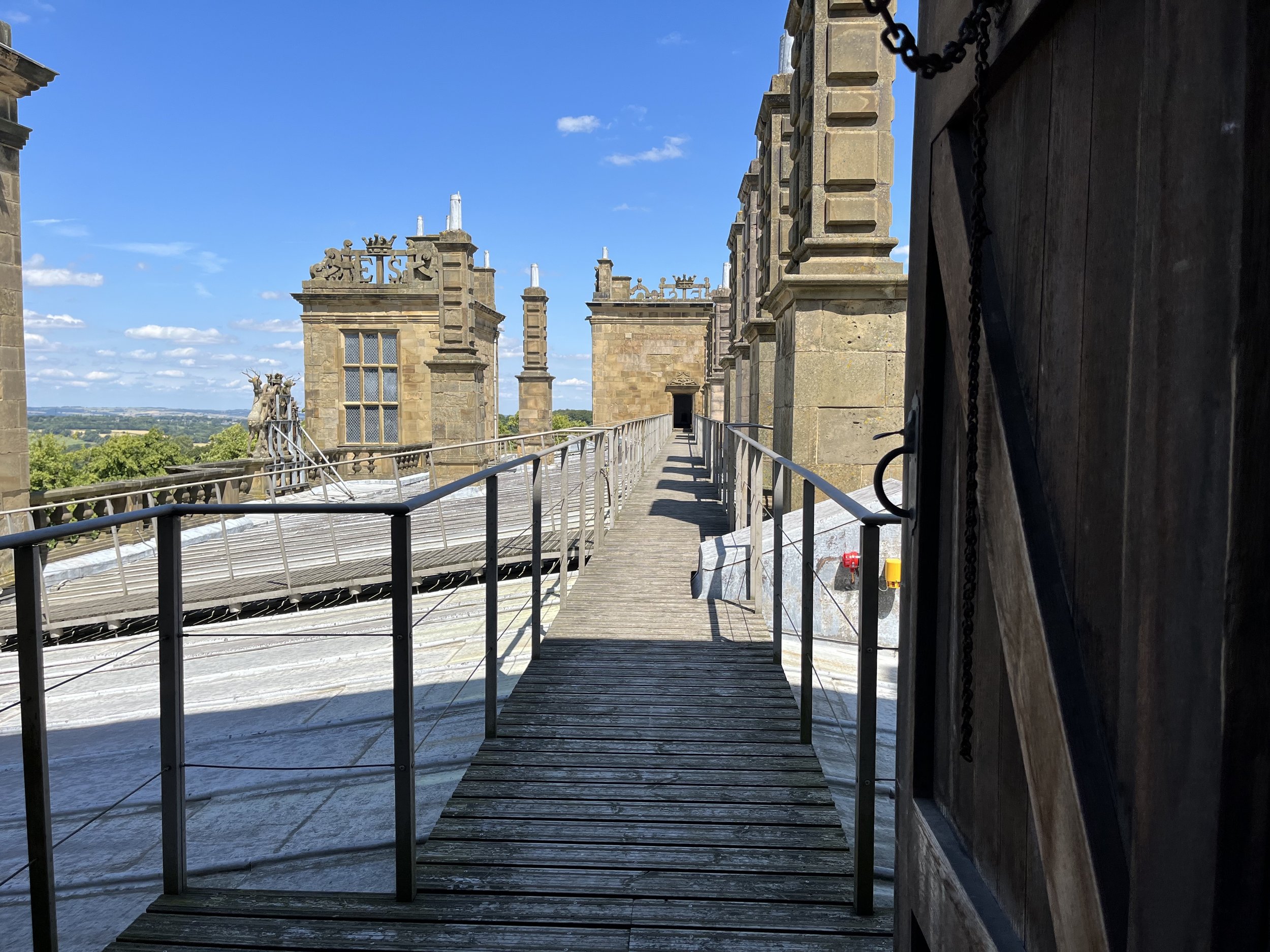

Seeing twenty-three country houses in a whirlwind sixteen days was an incredible, life-changing experience, both professionally and personally. It was an opportunity I will cherish for the rest of my life. I was pinching myself daily as we walked through these hallowed halls, often privately guided by decorative arts experts, historians, or the house owners themselves. We often darted into corridors and private rooms not accessible to the public which provided a unique and memorable exploratory experience. The subject matter ranged from Medieval painted stone, plasterwork ceilings, and Sèvres porcelain to Georgian architecture and everything in between. Throughout the program we reveled in various versions of the English country house, with a notable emphasis on Palladian inspired buildings, witnessing first-hand the English interpretation of Italian and Greek architecture and the remnants of the Grand Tour period. We, in effect, participated in our own miniature version of the Grand Tour which certainly is an educational rite of passage for museum and decorative arts professionals alike.

This theme of the “Grand Tour” was intricately woven throughout the course and was one of the key takeaways that I can directly relate back to the Philadelphia Society for the Preservation of Landmarks (PhilaLandmarks) house museums in Philadelphia. Samuel Powel (of the Powel House) was notorious for his extended Grand Tour to Europe, where he visited England, France, Italy, and the Netherlands as a young gentleman recently coming into his inheritance. I encountered similarities to Powel’s taste, albeit on a much grander scale, in the architectural features and décor at many of the country houses we visited. These elements were most notably visible at Uppark, Petworth, Kedleston Hall, designed by Robert Adam, and William Kent’s Houghton Hall. In looking back on my notebooks, my musings on the course are reminiscent of Samuel Powel’s 1761 Grand Tour journal from the Powel House Collection which highlights many grand buildings in Holland and compliments the fine tapestries and paintings Powel discovered during his travels.

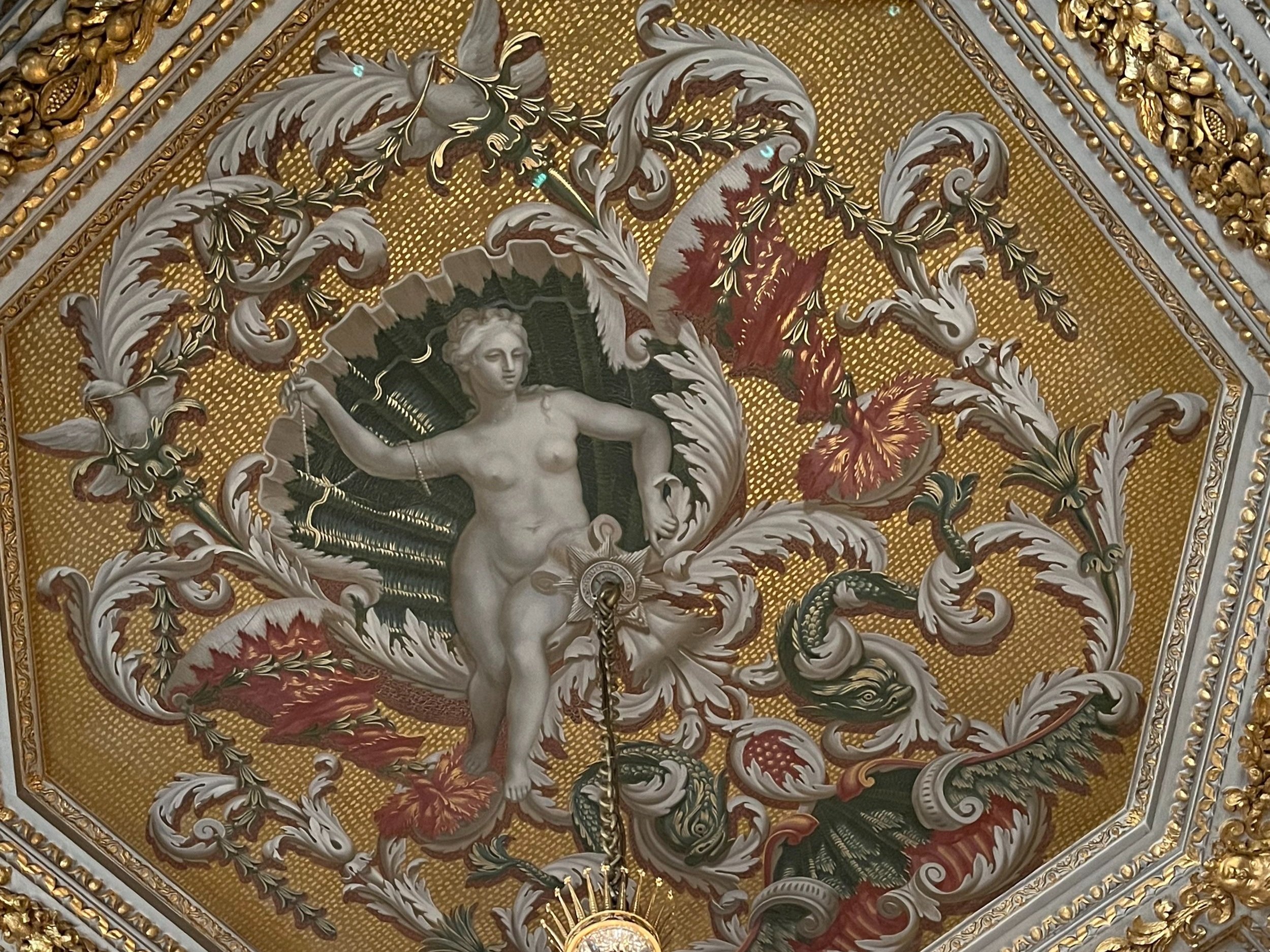

At Holkham Hall (1734-1762) in Norfolk, I was tickled to discover a pair of chimneypieces with Aesop’s fables. Adorned with the depictions of the “Sow and the Wolf” and the “Bear and the Bees,” these marble pieces were prominently featured above the two fireplaces in the elegant dining room located just off the main Marble Hall. Holkham Hall, built by Thomas Coke (1697-1759), 1st Earl of Leicester, is one of the best Palladian-style buildings in England. The stories carved in marble warn the onlooker that “there are no snares so dangerous as those that are laid for us under the name of good offices,” and “the weakest united may be strong to avenge,” respectively. The cautionary scenes reminded me of the Powel House’s “Dog and the Piece of Flesh” fable brilliantly fixed on the ballroom’s pine chimneypiece by London trained carver, Hercules Courtenay, and warns the onlooker of the perils of greed. Courtenay modeled his rendition of the fable after one of Francis Barlow’s editions of Aesop, issued in 1666 and 1687. [1] With a little research, it appears the marble carvers at Holkham likely did the same. I was delighted to find another depiction of one Aesop’s fables the “Fox and the Crane” on the chimneypiece in the small drawing room at Uppark. The proverbs and the adages of Aesop’s fables rose in popularity during the 18th century and served as inspiration for many mid-century rococo architectural interiors of the period. [2]

Holkham Hall: Sow and the Wolf

Holkham Hall: Bear and the Bees

Powel House: Dog and the Piece of Flesh

I also found it quite interesting that, much like in the United States, the deprivatization of the English country house and the preservation movement surrounding this effort occurred at the same time as the boom in innovation during the Industrial Revolution. While no direct correlation was made to this idea during the course, we saw notes of its influence with design reform in the Arts & Crafts movement, which highlighted the desire to return to nature and away from the mechanized modern world. The birth of the preservation movement in the United Kingdom started with the Ancient Monuments Protection Act in 1882 which served as the first vehicle for protecting prehistoric sites. By 1913, the act was amended to widen the scope of “historic monuments” to include later edifices and the protection of the wider landscapes surrounding the monuments.

Similarly, the preservation movement in the United States goes hand in hand with the development of a national historic consciousness born out of the rapid changes of the Industrial Revolution and the second massive influx of immigration in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. No matter how out of touch it may seem today, these modern changes in culture and industry ignited a unified consciousness to cling to the nation’s colonial foundation and spurred the re-emerging narrative that sparked the Colonial Revivalism movement. Meanwhile across the Atlantic, English country houses suffered from the complexities in death taxes and the agricultural recession in the late nineteenth century, which resulted in dwindling estate income. The idea of offloading the responsibilities of the estate to entities like the National Trust offered a viable opportunity for the longevity of preserving the houses while simultaneously allowing the owners to maintain their wealth. Therefore, many country houses were turned over to the public with varying degrees of open hours and tourism. While this model is rife with intricacies that complicate the relationships between families and the National Trust (or similar entities), it has ensured that these historical treasures remain accessible to the public and preserved. Though I haven’t yet found much scholarship on the relationship between the Industrial Revolution and the preservation of English country houses, I feel that there is a similar connection around historic consciousness, much like the historic preservation movement in the United States.

Overall, the Attingham Summer School Course has furthered my professional career by giving me a wealth of information to apply to our four historic house museums. It also has greatly increased my network of museum professionals and decorative arts experts. From practical matters regarding lighting dark historic rooms and keeping vermin out of gardens, and complex business models to historic collection interpretation and decorative arts education, every facet of the course challenged my thinking and encouraged me to view the work we do at PhilaLandmarks with a fresh, broader perspective.

[1] Edward Hodnett, Francis Barlow, First Master of English Book Illustration (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978), pp. 220–22. The book was initially printed in 1666.

[2] https://chipstone.org/article.php/683/American-Furniture-1996/Designs-for-Philadelphia-Carvers